One frustration I’ve had with task list applications on iOS and macOS is that they tend to hide where they store the data you’ve saved on it. That’s fine … until you find out that whoever made the app has decided to stop maintaining it.

You’re then stuck with a legacy app that is never going to get updated. This becomes an issue if you depend heavily on the application, and your operating system regularly sends old applications to the trash heap by labeling them as "incompatible" with the current version of your OS.

Here, I’ll be showing you how to write a small Go program to get your data out of applications like Clear. The goal here is to show:

-

How easy (or difficult, depending on your inclination) it is to use the Go programming language.

-

How a bit of problem solving can give us a bit more control over the devices/applications we use on a daily basis.

-

Why it’s important to get data out of an app like Clear.

1. What’s Clear?

Clear is a simple todo app that I’ve been using since circa 2013. To date, I’ve saved close to 2000 notes on it and still use it for very quickly jotting down ideas. The company that made the app has since taken it off their website, and my last email from their customer support [1] pointed me to a post on another company’s website which appears to be developing a follow up to the original. I’m not blaming them; apps are expensive to maintain, and everybody has to move on at some point of time. But that’s a lot of insecurity there — if a change in iOS or macOS renders the app unusable, or even worse, inadvertently removes data from my Clear installation, then I’d be in a lot of trouble.

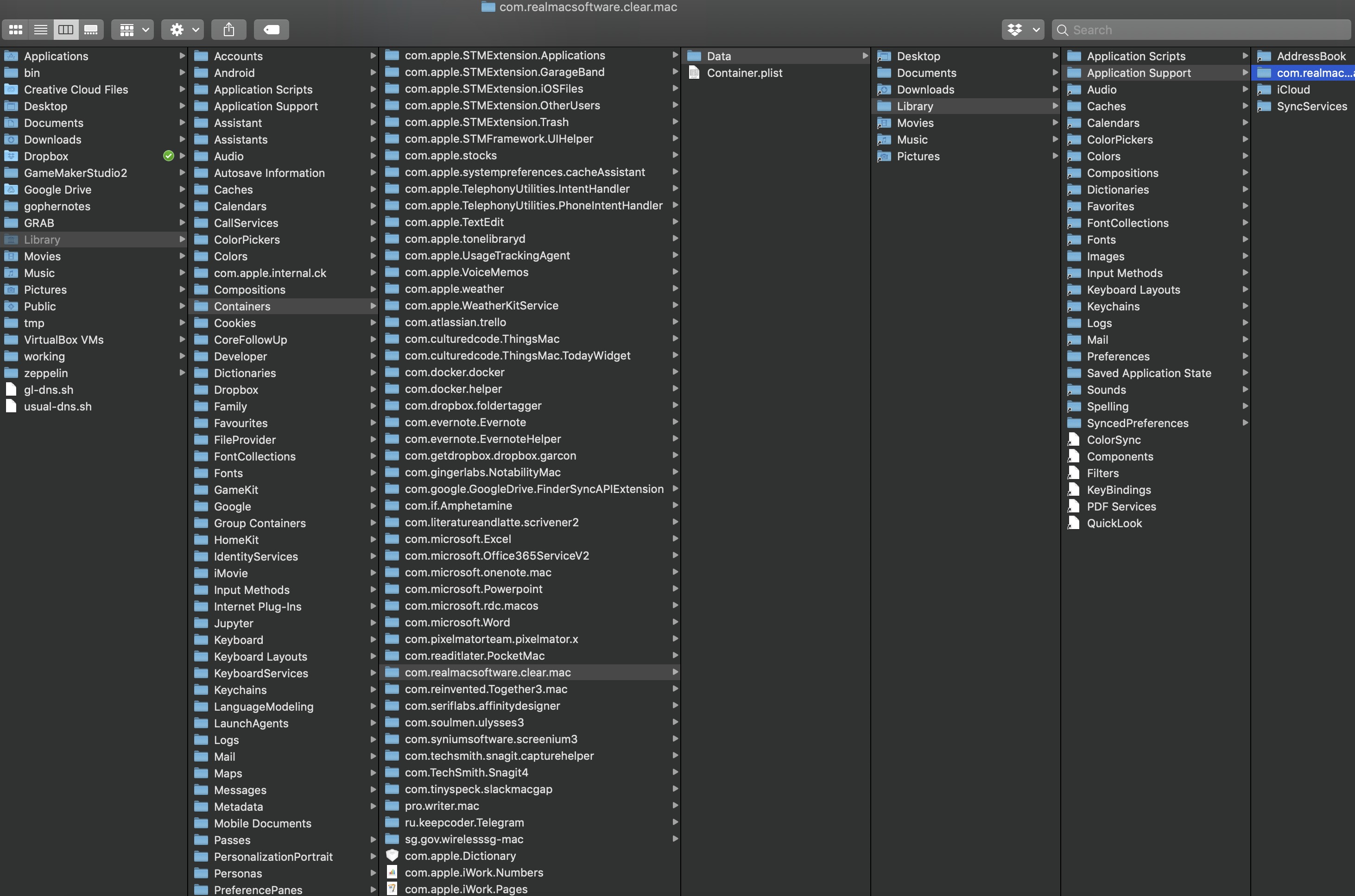

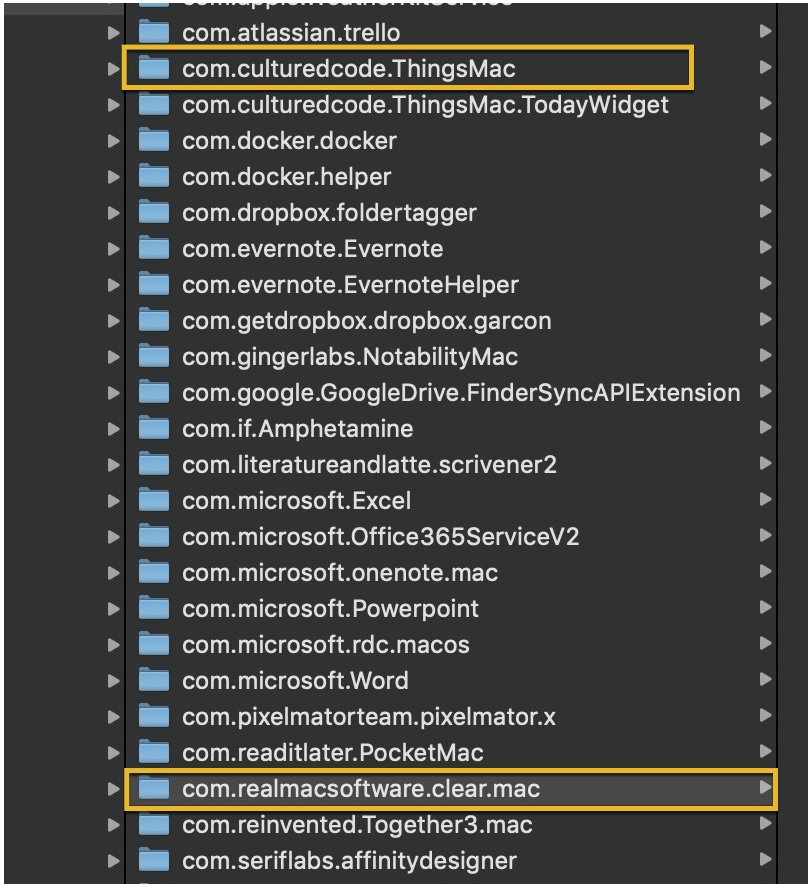

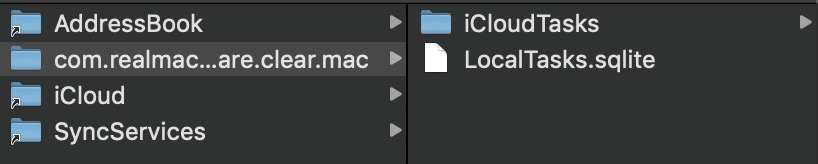

The straightforward solution would be to run backups on the backing database. But what to run backups on? There isn’t an export function, and whatever it’s storing its data on is not readily obvious to the layperson. So I got digging, and found out that Clear uses a SQLite database buried deep inside the ~/Library/Containers folder.

I’ve taken a cue from https://github.com/AlexanderWillner/things.sh, which also runs on a SQLite database, and wrote a small program that extracts data directly from the application database and saves it to a text file. You can check it out here: https://github.com/zeddee/clear-archiver.

$HOME/Library/Containers/com.realmacsoftware.clear.mac/Data/Library/Application Support/com.realmacsoftware.clear.mac/LocalTasks.sqlite.

LocalTask.sqliteThen, you can decide if you want to do it the easy way and use an application like https://sqlitebrowser.org/ to open your .sqlite file, or you can be like me and choose to write a Go program to do it.

2. Explaining SQLite

Databases are usually complex things that require lots of computing resources to run. Most web services, such as Wordpress, run a complex RDMS (relational database management system) behind the scenes to store everything, from your user details to your posts and media.

If you’ve ever tried to move your stuff out of a Wordpress installation, you know that getting data out of Wordpress is not a matter of copying files from one location to another — there’s an easy-to-mess-up process of dumping content from one Wordpress database, and then loading it into another. But Wordpress is also one of the most popular content management systems because from within the application, it’s easy to create, edit, and manage a large amount of content. It’s just that outside of it, everything is hidden behind a brick wall.

When you neither expect to manage a large amount of content nor you want to expend the resources to maintain a full-fledged database, then you can turn to embedded databases like SQLite and BoltDB.

Embedded databases are databases that run off a single file — no infrastructure to set up, no servers to maintain. This is useful when your application doesn’t need to share its data — or if it has to, doesn’t need to allow many parties to read from and write to it at the same time. It also means that it’s easy to move your data around: you can’t really move a Wordpress site from one server to another because your content is stuck in the database server (well you can, but with planning and wrangling with virtual machines etc.); but you can just copy entire applications with their sqlite databases onto a USB drive, and it’ll still be able to run from there.

When you build an application that uses a SQLite database, your data is saved to a .sqlite file that you can move to another system and use with zero setup. No servers, no login credentials (you can set up credentials if you need them, but we won’t deal with that right now). It’s almost like using an Excel spreadsheet — except that you’ve got to do a bit more work to use it.

Other than being small, SQLite databases are very easy to back up. You just make a copy of the .sqlite file, and that’s it. That’s probably why Things and Clear are both using it — because having your database stored in a single small file makes it very easy to sync across cloud services like iCloud. And SQLite databases really do stay small. My Clear instance has over 2000 records, and the resulting .sqlite file is just around 750kb.

3. Why write a program to get the data out?

I wrote https://github.com/zeddee/clear-archiver because:

-

I was bored.

-

I’ve been learning how to interact with databases with the Go programming langauge, and wanted to try and make something practical.

But more importantly, it allows me to automate what would otherwise be a tedious backup process. Instead loading up a .sqlite file into an application to read it, and then exporting that data, I just run clear-archiver to dump data out from Clear.

4. Getting started

Everything here is written for macOS. The concepts are exactly the same, but details such as what to run in the command-line would vary between platforms. That being said, you’ll also need to be comfortable with the Terminal. If you’re not, read this primer on how to use the terminal to help you get started.

In addition, you’ll want to have a SQLite3 database ready to work with. This guide will assume that you’ll be working with your Clear database: copy from the following directory to your project directory so that you’re working on a safe copy of the database instead of the original.

cp ~/Library/Containers/com.realmacsoftware.clear.mac/Data/Library/Application Support/com.realmacsoftware.clear.mac/ <your_project_directory>|

Tip

|

If you don’t use Clear, or don’t want to mess with your Clear database, but still want to follow along, you can use any other SQLite database. You can get a sample database to work with here: http://www.sqlitetutorial.net/sqlite-sample-database/ |

First, make sure you have the latest version of https://golang.org and https://sqlite.org/index.html installed.

To check, run in the terminal:

go version #=> go version go1.11.2 darwin/amd64

sqlite3 --version #=> 3.24.0 2018-06-04 14:10:15 95fbac39baaab1c3a84fdfc82ccb7f42398b2e92f18a2a57bce1d4a713cbaaplNext, install the SQLite3 drivers for Go with go get. Run:

go get -u -v github.com/mattn/go-sqlite35. Checking your .sqlite file

The first thing we need to do is to check if our SQLite database is valid. That is, we need to make sure that we’re able to interact with the database file in the first place. We do this by opening the database file with the sqlite3 command:

# Usage: sqlite3 <location-of-db>

sqlite3 ~/data/database.sqlite|

Note

|

If you’re using the Chinook database from http://www.sqlitetutorial.net/sqlite-sample-database/, notice that they’ve provided a .db file instead of a .sqlite file. The extension doesn’t matter, so long as you can open it with the sqlite3 command.

|

If the command runs successfully, your Terminal displays the SQLite console:

SQLite version 3.24.0 2018-06-04 14:10:15

Enter ".help" for usage hints.

sqlite>To make sure that you’re actually interacting with the database and not a dummy file, we’ll run a few queries.

First, display all the tables in the database by running .tables:

.tables

#=> If you run this with the Chinook database, sqlite lists the following tables.

# completed_tasks modelmeta_int tasks

# lists task_reminders versionNext, list the contents of a table by running SELECT * FROM <table_name>;:

# Remember to include the trailing ";"

SELECT * FROM tasks;Did your commands work? Congratulations, you’ve successfully run SQL queries on a database!

6. Writing your Go program

Now we’re getting to the meaty part.

Create a folder for your project. In it, create a file called main.go and open it in your text editor of choice. I recommend using VSCode with the Go tools installed.

6.1. Connect to the SQLite database

In main.go, add the following lines of code:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

package main

import (

"database/sql"

"fmt"

"log"

_ "github.com/mattn/go-sqlite3"

)

func main(){

dbLocation := "./data/database.sqlite" // Make sure you have this point at a valid SQLite file

db, err := sql.Open("sqlite3", dbLocation)

if err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

defer db.Close()

err = db.Ping()

if err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

} else {

fmt.Println("Contacted database successfully!")

}

}

What we’re doing here is:

-

Importing the

database/sqlpackage from the Go standard library. -

Importing SQLite3 drivers for Go from

github.com/mattn/go-sqlite3. -

Opening a database connection with

sql.Open(), and assigning that connection todb. -

Checking if we’re able to connect to the database with

db.Ping(). Ifdb.Ping()runs successfully, we tell the terminal to display a success message; if not, we display an error.

|

Tip

|

If you’re not familiar with Go, then the idea of having to constantly check if err != nil would be weird. Go treats errors as values instead of exceptions, which allows you to use them for flow control in your application. It also forces you to handle all errors explicitly, instead of hoping that nothing goes wrong in your application. You can skip an error check by replacing an err value with _. For example, instead of writing db, err := sql.Open("sqlite3", dbLocation), you can write db, _ := sql.Open("sqlite3", dbLocation) (but we don’t recommend that).

|

When you’re done, test your program by running in the terminal:

go run main.go

#=> 2018/11/23 16:49:01 Contacted database successfully!6.2. Get column headings from a table

Let’s do something more useful. We don’t know how the data in each table is organized, so we’d need to find out what’s supposed to go into each column.

Let’s say that we want to find the column names for the tasks table. Here’s how we do it in Go. In main.go, at the bottom of your main() function, add the following lines of code:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

func main(){

// The code we wrote earlier...

rows, err := db.Query(`SELECT * FROM tasks LIMIT 1`)

if err != nil {

fmt.Println(err)

}

colNames, err := rows.Columns()

if err != nil {

fmt.Println(err)

}

fmt.Println(colNames)

}

Here, we’re:

-

Running a SQL query that (1) selects all columns from the

taskstable, and (2) returning only one (the first) row. This gives us arowsobject. -

We call the

.Columns()method on therowsobject (by writingrows.Columns()), that gives us a list of column names for thetaskstable. -

We assign this to

colNames, and print this out.

Run go run main.go in the terminal again, and you’ll see the column headings of the tasks table: [id identifier list_identifier title prev_identifier next_identifier].

But this only gives us the column headings, but not the data types for each column.

6.3. Get column data types

We also need the data types that are assigned to the columns of a table. Each column in a table has a specific data type that must be strictly followed when saving data to the database: if a column is assigned a TEXT data type, then you can only save text "strings" it. Attempting to save a number to that column would produce an error. When we read this data out with our Go program, we need to tell Go what exactly what data type to expect from the database, or it would give us an error. It’s also how reading information from databases with Go is like: it’s strict about the information that we read and write to a database (and rightly so).

To get the data types of each column, we’ll modify the code we wrote earlier to get column names from the table. Instead of rows.Columns(), we’ll add new code that calls the rows.ColumnTypes() method instead:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

func main(){

// ...

cols, err := rows.ColumnTypes()

if err != nil {

fmt.Println(err)

}

for index, value := range cols {

fmt.Printf("Col %d: %+v", index, value)

}

}

We get a list of ColumnType objects from our rows.ColumnTypes() call, which we assign to cols. We then loop over the list and print out each ColumnType object to get something like this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

Cols 0: &{name:id hasNullable:true hasLength:false hasPrecisionScale:false nullable:true length:0 databaseType:INTEGER precision:0 scale:0 scanType:<nil>}

Cols 1: &{name:identifier hasNullable:true hasLength:false hasPrecisionScale:false nullable:true length:0 databaseType:TEXT precision:0 scale:0 scanType:<nil>}

Cols 2: &{name:list_identifier hasNullable:true hasLength:false hasPrecisionScale:false nullable:true length:0 databaseType:TEXT precision:0 scale:0 scanType:<nil>}

Cols 3: &{name:title hasNullable:true hasLength:false hasPrecisionScale:false nullable:true length:0 databaseType:TEXT precision:0 scale:0 scanType:<nil>}

Cols 4: &{name:prev_identifier hasNullable:true hasLength:false hasPrecisionScale:false nullable:true length:0 databaseType:TEXT precision:0 scale:0 scanType:<nil>}

Cols 5: &{name:next_identifier hasNullable:true hasLength:false hasPrecisionScale:false nullable:true length:0 databaseType:TEXT precision:0 scale:0 scanType:<nil>}

|

Tip

|

The ColumnType object is a "struct", which is one of the ways Go stores a collection of data. We can print out the contents of a struct by using the %+v string template to print out its fields and its labels: fmt.Printf("%+v", <ColumnType>)

|

From our output, we can see that each column in the table is described by a struct. We’ve already got the contents of the name field with our rows.Columns() call. Now, we just need contents of the databaseType field. We can get this by modifying our for loop:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

func main(){

// ...

cols, err := rows.ColumnTypes()

if err != nil {

fmt.Println(err)

}

for index, value := range cols {

fmt.Printf("Cols %d: %+v", index, value.DatabaseTypeName())

}

}

When we run main.go again, it gives us a list of columns and their data types:

Cols 0: INTEGER

Cols 1: TEXT

Cols 2: TEXT

Cols 3: TEXT

Cols 4: TEXT

Cols 5: TEXTNow we know that the first column (Column 0) is an INTEGER or a numerica type, and all other columns are TEXT or text string data types. Now we’ll be able to tell Go what data types it should expect when extracting data from the database.

|

Tip

|

To learn more about data types in SQLite, see https://www.sqlite.org/datatype3.html |

6.4. Read data from the database

We’re ready to get data out of our Clear database. First, empty out your main() function except for these lines of code:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

func main(){

dbLocation := "./data/database.sqlite" // Make sure you have this point at a valid SQLite file

db, err := sql.Open("sqlite3", dbLocation)

if err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

defer db.Close()

}

Now that we’ve got a clean slate, we’ll create a struct type that works as a template to store data we’re extracting. Add this code above the main() function:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

type Task struct {

ID int

Identifier string

ListIdentifier string

Title string

PrevIdentifier string

NextIdentifier string

}

func main(){

// ...

}

Then, we can add the following lines of code to main() itself:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

func main(){

// ...

rows, err := db.Query(`SELECT * FROM tasks`)

if err != nil {

log.Fatal(err)

}

var allTasks []Task

for rows.Next(){

r := Task{}

rows.Scan(&r.ID, &r.Identifier, &r.ListIdentifier, &r.Title, &r.PrevIdentifier, &r.NextIdentifier)

allTasks = append(allTasks, r)

}

fmt.Printf(allTasks)

}

Run your program in the terminal: go run main.go. If everything works, you should see the contents of your tasks table displayed.

What’s happening here is that we’re looping over all the rows we’ve gotten from our SQL query (db.Query()) with for rows.Next(){}.

For each row, we’ve set up a temporary data storage structure r that takes on the shape of our Task struct type. We then "scan" the row and tell Go to slot the values we’re getting from the scanned row into r. We then add this particular r to our list of tasks: allTasks, and move on to the next row. When we run out of rows, rows.Next() will evaluate to false, and our program will stop looping over rows.

By then, we should have saved data from all the rows to our allTasks list, which we then print out to the terminal.

7. Postscript and the Why

You’re done! You’ve written a small Go program that reads from a SQLite database and prints its contents out to the terminal.

Right now, your program will be missing stuff like the ability to save that data into a CSV file. We’re not getting into that in this guide, but you can see how it’s done in https://github.com/clear-archiver. For now, you can save your program’s output to a file by "piping" the output:

# Pipe output to your clipboard, so you can paste it into a text editor

go run main.go | pbcopy

# Pipe output to a file

go run main.go > output.txtBut you get the idea. We’ve gotten data out of our Clear SQLite database, but you can use this method to get data out of any SQLite database.

More importantly, it’s an example of how we are able to create data mobility for ourselves if we are able understand and dissect the systems that we rely on. It’s also to show that data mobility is not difficult to implement.

Under the GDPR, which kicked in May this year, the ability to export your data is now required by law in the EU. This means that it is illegal (under the GDPR) for any vendor to lock your data into their service. Now that you’ve read this, you also know a bit more about how "technically feasible" it is to move data out of what is usually regarded as an opaque medium (i.e. applications and databases).

If there’s one thing that I want you to take away from this article, it’s that you should insist on control over your data. Because it’s not hard. Until next time.